Analyzing the impact of COVID-19 on education in Spain: A look at PIRLS 2021 test results

Lucía Cobreros Vicente, Lucas Gortazar

17 May, 2023

In two sentences:

→ The PIRLS 2021 test reveals a 7-point decline in reading achievement in Spain linked to school closures during the pandemic. This decline (significant at 95% but not at 99%) is more moderate than that experienced by many neighbouring countries, which corresponds to the school closure period, shorter in our case.

→ A greater budget and focus on remedial tutoring, as well as socio-emotional support, are essential to mitigate the impacts of the pandemic and ensure equity and quality of education.

The recent release of PIRLS 2021 (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study) test data by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) provides a valuable comparative analysis of the reading achievement of 10-year-old students around the world. In light of the unprecedented challenges that the COVID-19 pandemic has posed to education, it is crucial to understand how these have affected learning. In this article, we will discuss the most relevant findings for Spain and its context.

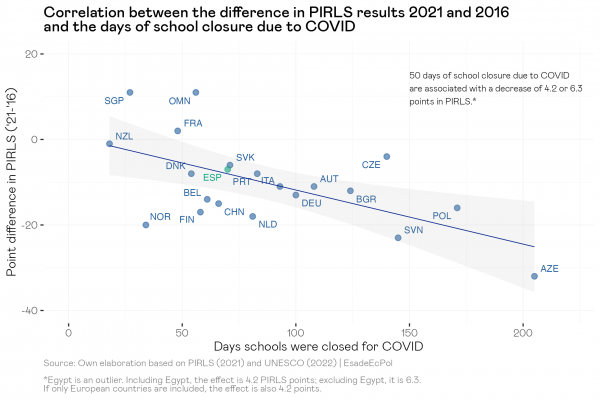

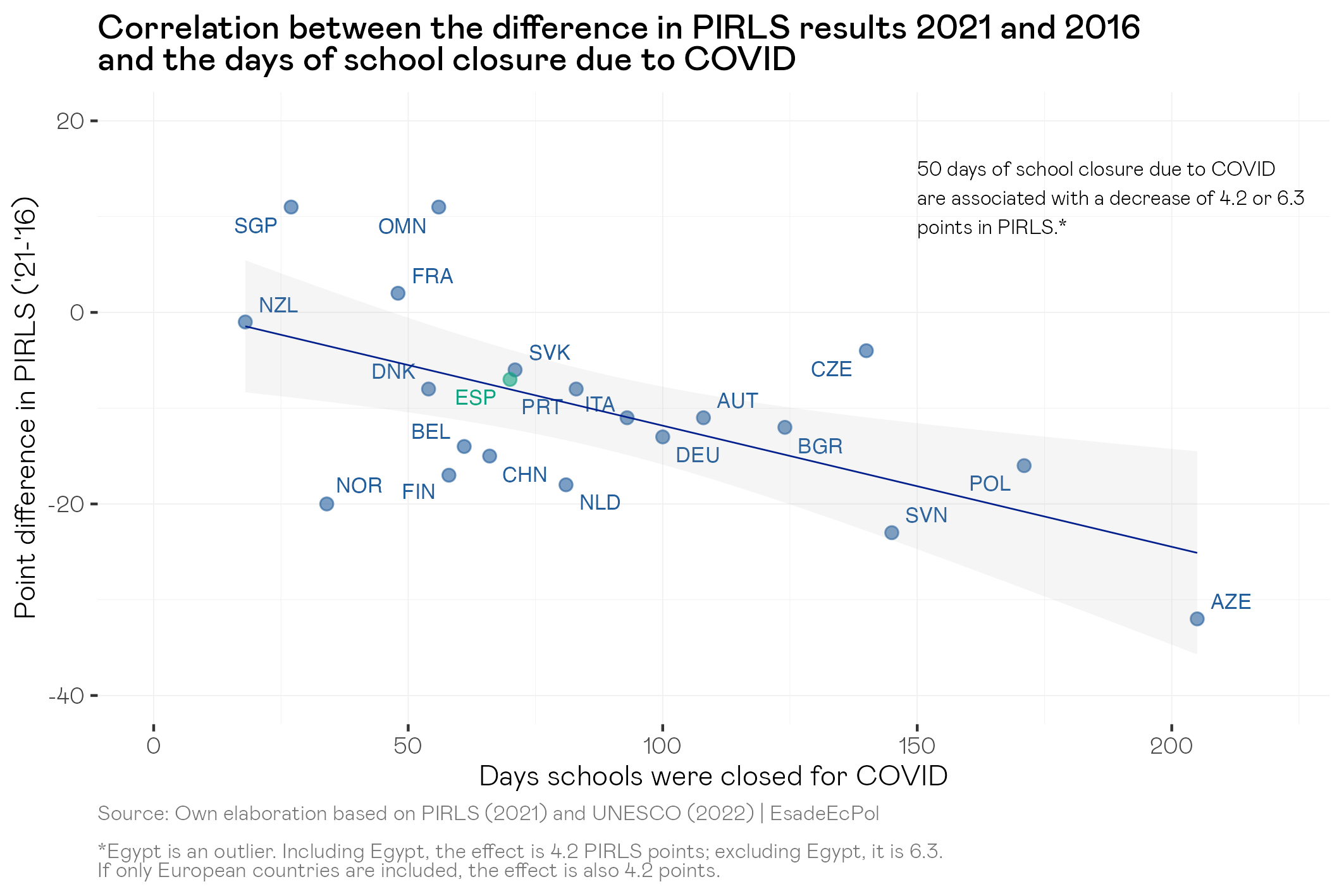

Since the last assessment in 2016, before the pandemic, global results have evidenced widespread drops in learning. In Spain, although a drop is also observed (7 points), it has been smaller than in many neighboring countries. This drop is statistically significant at 95% but not at 99%, so it is practically within the margin of error. Cross-referencing these data with the number of days of school closures in each country due to the pandemic, a negative and significant relationship is seen: every 50 days of school closure is associated with a decrease of between 4.2 and 6.3 points in PIRLS.

In the area of socioeconomic inequality, the results are encouraging. The socioeconomic gap in Spain is smaller than the international average, placing it as a more equal country than many Nordic countries. Likewise, the gap between the scores of the highest and lowest decile is also significantly smaller.

However, a surprising finding is the negative perception of parents about the impact of COVID-19 on their children’s education, despite the fact that academic results have been substantially better than expected in the context of the pandemic.

It is important to insist that these data should be contextualized. Although the decline in outcomes in Spain is significant, it was milder than in many other countries, and the effective reopening of the 2020/21 school year seems to have played a key role in this.

In addition, Spain has the peculiarity that students taking the test are younger (9.9 years) compared to the global average (10.2 years), suggesting possible room for improvement in students’ reading maturity.

As for the international ranking, although it is not the most relevant indicator, Spain is on a par with countries such as Germany, France or Portugal, who obtain better results in the PISA reading test. This invites reflection on what happens between primary and secondary education in Spain, where some problems seem to arise.

Finally, the gap in reading scores in Spain, comparing students at the 90th percentile and the 10th percentile, is 177 points, significantly lower than in countries such as Belgium, England, Denmark, Germany, the United States, Finland or Sweden.

What to do

In sum, the PIRLS 2021 data, while reflecting the challenges posed by the pandemic, also reveal positive aspects in the Spanish education system, especially in terms of equality. The task ahead is to continue working to minimize the impact of the past crisis, prevent the impact of future crises, and further strengthen the equity and quality of education in Spain.

In this sense, and as we had the opportunity to discuss in our first in-depth analysis of learning losses during the pandemic and the policies to remedy them, individualized or small group reinforcement measures, such as tutoring, have proven to be effective nationally and internationally. The Orientation and Reinforcement Program for the Advancement and Improvement of Education (PROA+) is a key instrument in educational reinforcement in Spain. However, with a budget of 120 million euros per year, per capita investment adjusted for GDP and number of students is considerably lower than in other countries. Countries such as the Netherlands, the United States and the United Kingdom invest up to ten times more in similar reinforcement programs. In fact, in many autonomous communities in Spain there are still few programs that are systematic, continuous and well-structured. A concerted effort is needed to expand and improve the supply of tutoring throughout the country, ensuring that students have access to this valuable educational resource.

In addition, it is crucial to address the socioemotional aspects of learning, not just academics. The pandemic has had a significant impact on student well-being, and it has been shown that the inclusion of social-emotional mentoring in educational programs can help mitigate these effects. At the same time, education is not just an individual matter, but involves the entire community. Therefore, programs aimed at families and partnerships with the environment should be encouraged, especially in vulnerable areas.

Finally, it is important that educational reinforcement measures be integrated into the regular operation of schools, rather than being considered as extracurricular activities. Likewise, vocational training, often overlooked in the design of these measures, should not be overlooked and should receive special attention. And, of course, better evaluation and monitoring of these educational policies and practices is needed to ensure their effectiveness and adjust them as necessary.

Economist focused on education, with interest in health, gender and competition. Degree in Economics from the University of Cantabria, Master in Industrial Economics and Markets (UC3M).

View profile