The cost of access to “escuelas concertadas” (publicly subsidized, privately run) in Spain: the fees paid by families and their causes

Lucas Gortazar, Ángel Martínez, Xavier Bonal

23 Apr, 2024

Subsidized education is a central element of the Spanish educational system. While 67% of students attend public schools, nearly 30% attend publicly funded but privately owned centers, called “centros concertados”(and only 4% attend self-financed private centers). The “concertados” fulfills an instrumental function in the development of Article 27 of the Constitution: freedom of education. However, the other function of said article, the right to education, has not been fulfilled. As of today, there is no universal free access to “concertados”. In addition, in comparison with public schools, a much smaller proportion of students from low-income and migrant backgrounds attend these schools, which significantly harms equal opportunities and equity, one of its fundamental objectives.

The main reason for not providing free education is the financing system established for “concertado” centersand a more lax regulation of their services: both encourage the collection of fees, which are illegal in theory but common in practice. The phenomenon of fees has been widely discussed in the public debate in recent decades, with extreme positions dominating: on the one hand, it is suggested that subsidized schools should disappear, with their students being taken over by purely public or private centers, and on the other hand, more money is demanded for the sector without any compensation, under the banner of educational freedom. Analysis and research to date have been scarce, superficial, and, on occasion, biased. Thus, they have favored these extreme positions and a homogeneous vision of these publicly funded and privately run schools, ignoring any diversity within it.

In this report, we present for the first time a complete, in-depth, and reliable analysis of the fee phenomenon among “centros concertados”. To do so, we use two databases prepared by the National Statistics Institute (INE): the first looks at the phenomenon from the side of fee payment (families) and the second from the side of collection (schools). Both because of their statistical representativeness and their breadth, they are the only sources that allow us to address the issue with the necessary methodological rigor. The consistency between both data sources is very high and shows similar patterns and magnitudes of the phenomenon.

The most important result is that contrary to what the public debate to date has suggested, we are faced with a sector that is more diverse than monolithic, both from the territorial point of view (each autonomous community has a different model) and from the point of view of the collection of fees and the most probable reasons why those schools that charge them decide to do so.

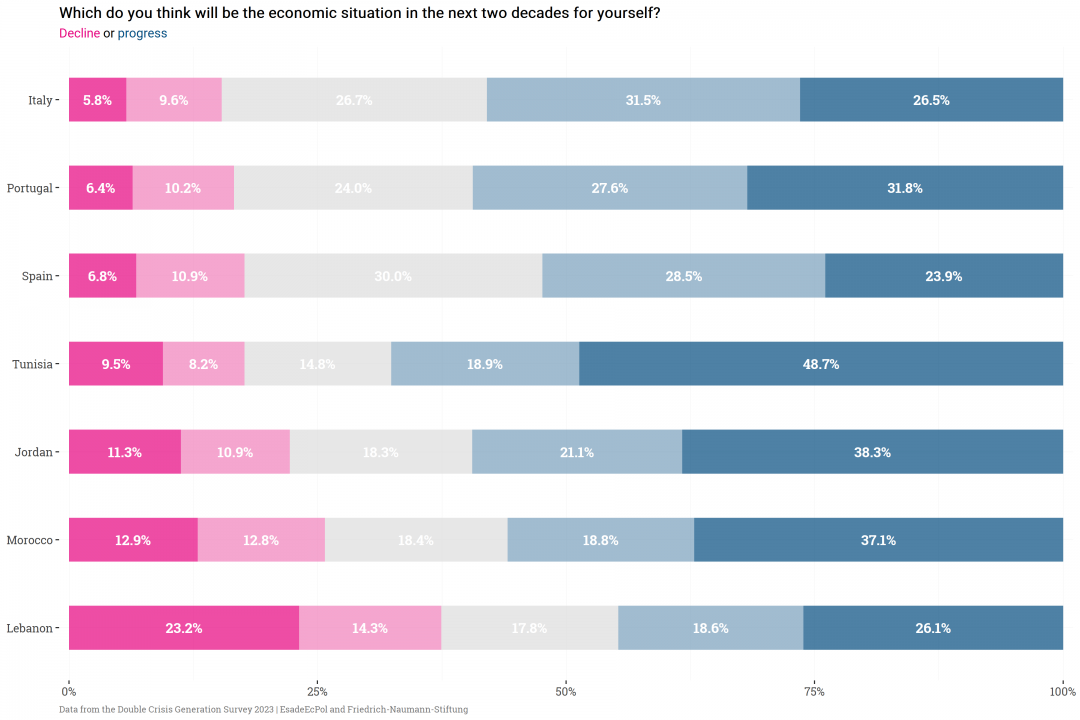

First, we study the payment of fees in the stages of the Second Cycle of Pre-school, Primary, and ESO by families. From the Household Expenditure Survey on Education (EGHE), last conducted in 2019/20, we find that:

- Depending on the stage of education, between 81% and 95% of students pay fees.

- The average fee is between €680 and €860 per year per student (including families who do not pay an equivalent fee of €0).

- This amounts to a total of between 947 and 1,186 million of euros for the three stages, depending on the definition of quotas used.

- There are 13% of students who do not pay fees in the stages considered, while 18% pay a very low fee (less than 20€ per month per student). On the other hand, the 10% of students with the highest fees pay 45% of the total expenditure.

- There are significant differences in the payment of fees according to family income: the 20% with the lowest income pay an average annual fee of €310, while the 20% with the highest income pay fees slightly above €1,000.

As for the autonomous communities:

→ The bulk of the fees (70% of the total) are concentrated in Catalonia, Madrid, and the Basque Country, where more than 90% of families accessing subsidized centers pay fees.

→ The percentage is somewhat lower in the case of the Valencian Community (82% of families) and is significantly reduced for Andalusia (60%).

→ The average fee per student per year (only for paying families) is €1,696 in Catalonia, €1,156 in the Community of Madrid, €959 in the Basque Country, €597 in the Community of Valencia and €453 in Andalusia.

→ Catalonia, followed by the Basque Country and Madrid, are the Autonomous Communities with the greatest homogeneity in the payment of quotas among families, while Andalusia shows the most unequal distribution.

Based on the Private Education Financing and Expenditure Survey (EFGEP), we analyzed the collection of fees by subsidized schools and the reasons why they do so. When calculating the economic result of the centers (i.e., income – expenses but without taking into account in the income the fees, nor in the expenses those not susceptible to be financed by the public coffers via concert) we find that:

- Funding is extremely unequal, with 20% of centers with negative or essentially zero financial results, another 50% with a positive financial result and less than 300 euros per student per year, and 30% that have a clear over-funding situation.

- The percentage of centers that charge fees ranges between 66% and 75%, depending on the educational stage.

- The likelihood of collection of fees and the size of the fee paid is highest in the worst and best-financed centers, and lowest in the intermediate financing zone.

- Ninety percent of the larger schools charge fees, while in medium and small schools, the proportion drops to between 60% and 70% of the schools: this phenomenon explains why there is a lower percentage of schools charging fees than the percentage of families paying them.

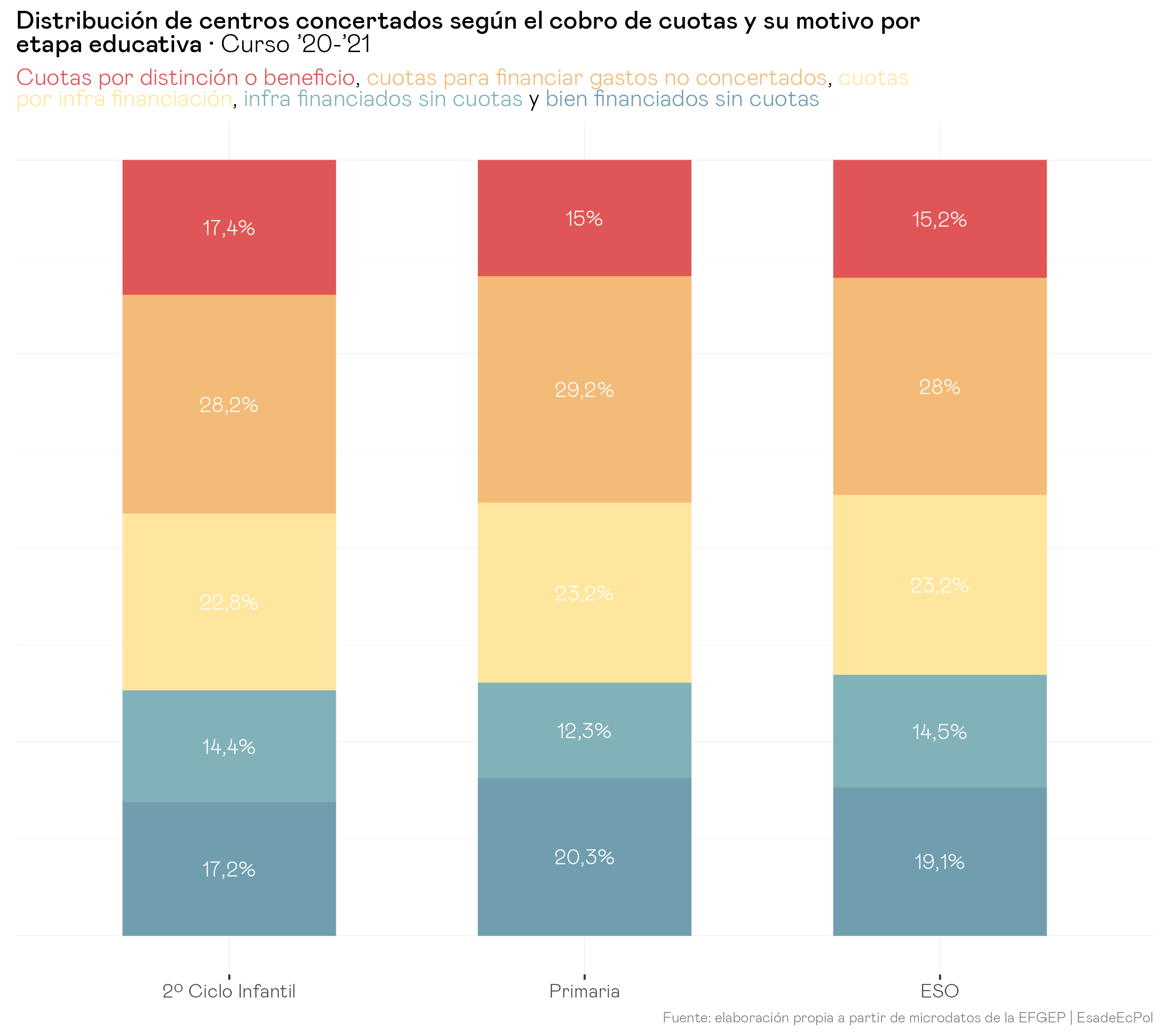

We explored the reasons why these schools charge fees. For this purpose, taking the economic result as a reference and adding a margin of 200 euros per student, we differentiate three possible situations: under-financed centers that charge fees to survive, adequately financed centers that charge fees to cover non-subsidized expenses (i.e., expense items not contemplated by the educational administrations and that allow for the expansion of the services offered) and well-financed centers that charge fees for differentiation or economic benefit. From here we can precisely segment, for each educational stage (Second Cycle of preschool, Primary, and ESO), all centers in the subsidized sector into five groups:

- Some 17%, 20%, and 19%, respectively, do not charge fees and are adequately financed.

- Some 14.5%, 12%, and 14.5%, respectively, do not charge fees and are under-financed.

- 23% across all educational stages do charge fees to cover the fact that they are underfunded.

- Some 28%, 29%, and 28%, respectively, do charge fees to cover non-contracted expenses.

- Some 17.5%, 15%, and 15% respectively charge fees for differentiation or economic benefit.

Finally, we performed a specific analysis of the five autonomous communities with the greatest presence of the subsidized sector, which shows us that:

- Andalusia is characterized by low funding compared to the national average, reasonably contained non-concerted expenditures in most of the funding distribution and, above all, the lowest level of quotas among all the Autonomous Regions considered.

- Catalonia shows a very polarized financing of the subsidized network (very well-financed or very poorly financed centers) and an almost universal collection of fees that responds with the same tool to opposite economic realities, whether they are under-financed (between 46% and 53% of centers depending on the educational stage) or those of differentiation of the offer or economic benefit (between 25% and 33% of the centers depending on the educational stage).

- In the Community of Madrid, there is a very strong relationship between fee collection and economic performance (better-financed centers have a greater probability of charging and collecting high amounts) and an enormous importance of center size in understanding the dynamics of fee collection. A low proportion of under-financed centers and a slightly higher proportion than the national average of centers that collect fees for reasons of differentiation from other centers or economic benefits are identified.

- The Valencian Community presents a positive relationship between fee collection and economic performance (especially in ESO), giving enormous importance to center size to understand the dynamics of fee collection and a high proportion of under-financed centers (almost 40%) with low fees that live in a precarious financial situation.

- The Basque Country has very high levels of funding in relation to the national average and the lowest proportion of underfunded centers. There is also a weaker relationship between the size of the school and the collection of fees, which are generalized and higher than the national average and, above all, great importance of non-subsidized expenses, the highest of all the Autonomous Communities analyzed, which constitute the main reason for the collection of fees. The Basque Country’s publicly financed & privately owned school is the paradigm, simultaneously, of a very good level of financing combined with high non-subsidized expenses.

The results show a remarkable consistency between what families pay and what schools charge, which reinforces the reliability of the analysis. It also provides us for the first time with a very precise estimate of the economic magnitude of fees in the subsidized sector, which ranges from 950 to 1.2 billion euros for the stages from 3 to 16 years of age. These results demonstrate the hypothesis of the diversity and complexity of the sector and show that the subsidized sector, treated as a unitary block, is in fact the sum of very diverse educational, geographic, social, and economic realities, to which it would be inappropriate to apply a one-size-fits-all educational policy.

The current system has reached a very stable equilibrium, where the incentives to change the situation are scarce for most of the actors involved, largely due to the low public investment in education in Spain: the existence of the “concertados” network reduces the pressure on the public spending of the educational administrations (among other things, because of lower salary costs per student and because they are larger centers), facilitates a system of social selection for higher income families in exchange for a co-payment and guarantees a broad demand that ensures the continuity of this semi-private sector. While the quality of subsidized schools is similar to that of public schools when we compare two centers with the same student characteristics, the conditions of access are very different: subsidized schools enroll students with a higher socioeconomic level and enroll immigrant students to a much lesser extent, which increases school segregation in Spain.

To ensure that this dual network does not become a major factor in school segregation and to ensure free access to publicly funded education, we propose the following measures:

- Develop a detailed analysis of the theoretical cost of school places in the public and subsidized sectors in all the autonomous communities.

- Extend the periodicity of data collection on private household spending and the cost of private education carried out by the INE.

- Audit non-contracted expenses, as well as the fees of those centers that, although they are not over-funded, are providing non-contracted services that are financed through fees.

- Develop mechanisms and incentives to put an end to the system of full subsidies for centers that are clearly over-financed and whose fees are high and which are considerably higher than the non-concerted expenses in their accounting. According to the simulations carried out, this would also make it possible to redistribute the available surplus to put an end to the under-financing that affects part of the subsidized sector.

- Supervise the cost of the school lunchroom in subsidized schools and bring it into line with the costs of public schools, to prevent it from becoming an indirect source of school funding.

- To regulate the contributions that families may make for complementary activities and other services, and to establish identical thresholds for public and subsidized centers.

Finally, and with the aim of guaranteeing a greater balance in the social composition of the student body of the two school networks, we propose the articulation of the instrument of “program-contracts” that would allow the ACs to incorporate economic amounts specifically linked to the objective of fighting against school segregation through economic means. To this end, the administration can encourage public and subsidized schools to meet certain standards both in terms of access for vulnerable students and in the services provided.

Doctor en Sociología y Licenciado en Economía por la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (UAB). Profesor titular y Director del Departamento de Sociología de la UAB.

View profile