Claudia Goldin: a detective and Nobel reference

Jenifer Ruiz-Valenzuela

13 Oct, 2023

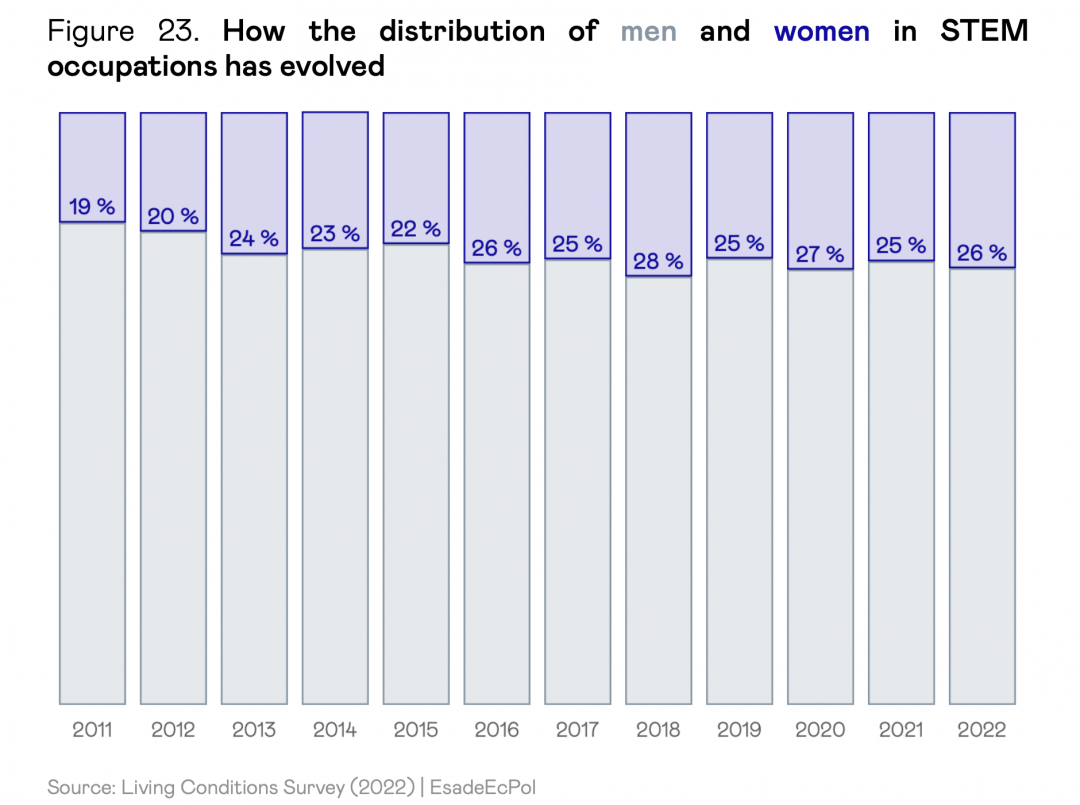

Last Monday morning, October 9, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that it was awarding the 2023 Alfred Nobel Memorial Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences to Harvard professor Claudia Goldin. In summary, the academy explained that Goldin was deserving of the prize for helping to understand the role of women in the labor market. With this simple sentence it is difficult to convey the weight that Goldin’s work has had on the discipline of economics. In its most direct impact, Goldin’s work is a pioneer in the economic analysis of the causes of the gender gap in the labor market. However, its indirect impact is of a magnitude that is difficult to calculate. As she explained hours after receiving the news of her award, Goldin has worked very hard during her career to change the representation of women in the economy. The role she has played as a reference for several generations of economists is indisputable. From the Gender and Inequality research line of EsadeEcPol, we wanted some of the economists who know Goldin’s work best to help us describe the special relevance of this Nobel.

Laura Hospido, senior economist at the Bank of Spain, tells us that, for her, “what is fundamental is everything we have learned about the dynamics of the gender wage gap. And is that, when we talk about the gender wage gap, we often talk about it as a single measure.” Hospido highlights that “even as an accurate statistic, the mean gap does not capture the complexity of the differences between men and women, because it does not show that the pay gap changes over the course of individuals’ careers. Moreover, the mean gap can mask the fact that some professions have large pay gaps and others have small ones. Claudia Goldin has had us look for the explanation of the wage gap by looking at the smoking guns, that is, the professions in which the largest gaps exist.”

In relation to this, Claudia Hupkau, professor at CUNEF University, highlights a quote, which I take the liberty of translating, from one of Goldin’s papers: “La brecha de género en el salario se reduciría considerablemente e incluso podría desaparecer por completo si las empresas no tuvieran un incentivo para recompensar de manera desproporcionada a las personas que trabajan largas horas y en horarios específicos.” (“The gender pay gap would be considerably reduced and might even disappear altogether if companies did not have an incentive to disproportionately reward people who work long hours and specific hours.“) (A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter; American Economic Review, 2014). Goldin and other economists have highlighted how, currently, a very large part of the gender gap in wages occurs with the arrival of the first son or daughter. Hupkau highlights the policy implications of Goldin’s work related to this fact: “what I would highlight from her research agenda is that she argues that closing the remaining gender gap – mainly related to having children – would require changing the way work is organized, not the way women are.”

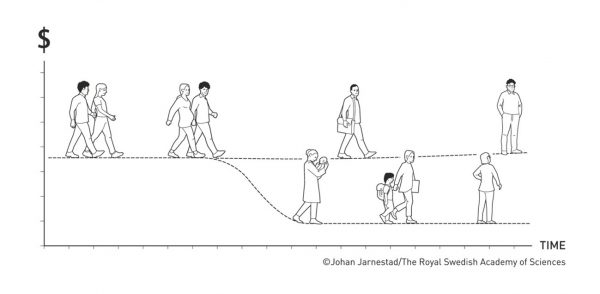

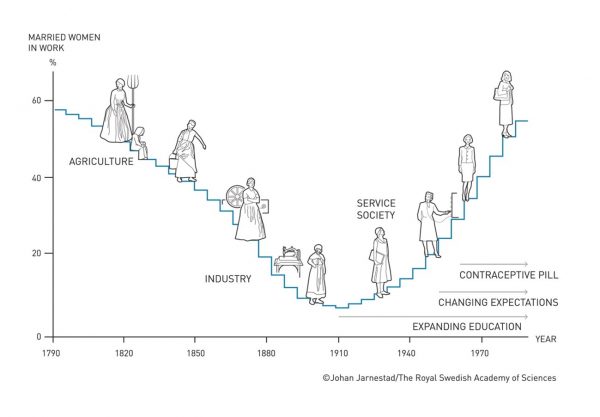

Lidia Farré, professor at the University of Barcelona, highlights Goldin’s work collecting and learning about historical data: “her work with historical data, which reveals that female participation is U-shaped, are very informative to understand that economic growth does not necessarily have to reduce gender inequality.”

“The current stagnation of the gender gap is related to the unequal distribution of household tasks and we need policies that incentivize men’s participation in caregiving and parenting,” Farré continues. “Work flexibility helps to improve the reconciliation between personal and family life, but it can be a double-edged sword as it could return women to the home and increase their specialization in domestic production.” In addition, Farré stresses that advancing in the understanding of the causes that lead to gender inequality in the labor market “is not only a matter of social justice, but also an issue of economic efficiency, since greater gender equality allows for a more efficient allocation of female talent“.

Also highlighting the role of working carefully with data, University of Barcelona professor Judit Vall: “Claudia showed that changes in women’s labor participation occurred by cohorts and that, therefore, if we look at a cross-section of women (at a given moment in time) we do not realize the real changes between cohorts. This, in turn, helps to understand why changes in these variables occur so slowly: because they occur by cohorts deciding their educational levels at early ages, which determines their labor participation for the rest of their lives.” To learn more about this, I recommend reading the article published in 2006 to which Judit refers (The quiet revolution that transformed women’s employment, education, and family; American Economic Review, 2006).

Finally, Yarine Fawaz, researcher at CEMFI, reflects on Claudia Goldin’s role as a popularizer, for example by writing books such as ‘Career and Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity’: “Beyond her most famous articles published in the best economics journals, her books allow us to discuss the latest advances in explaining gender gaps with those who do not have a PhD in economics, but are interested in understanding why women continue to earn less than men despite having a higher level of education. Their answers, including part-time work as women’s ‘preferences’ to be able to reconcile work and family, or the unequal division of domestic work between men and women, are very intuitive for the vast majority of women.”

From the Gender and Inequality line of EsadeEcPol we want to thank these five great economists for helping us understand that the Nobel to Claudia Goldin is more than a Nobel to a new economic model or specific results. It is also a Nobel that recognizes the importance of collecting data, disseminating results and attracting more researchers to the discipline, in order to keep pushing the boundaries of knowledge. They are the clear example of the latter, and this is indicated by many of their publications in the field of gender economics.

· · ·

In case you want to deepen and expand, here we leave you readings of the work done from the Gender and Inequality line of EsadeEcPol.

→Work and children in Spain: Challenges and opportunities for equality between men and women · Claudia Hupkau y Jenifer Ruiz-Valenzuela · March, 2021

→ Gender gaps in the labor market during the pandemic · Claudia Hupkau y Pablo García-Guzmán · March, 2022

→ What else can we do to reduce the gender gap in the labor market? · Jenifer Ruiz-Valenzuela, Claudia Hupkau y Lucia Cobreros · October, 2023, in the book ‘Un país posible’.

→ Webinar: evidence to reduce gender gaps · Libertad González, Judit Vall, Ana Moreno-Maldonado, Irene Unceta, Claudia Hupkau, moderated by Jenifer Ruiz-Valenzuela and presented by Lucía Cobreros · March, 2023

→ How to increase women’s access to scientific and technical disciplines in higher education? · José Montalbán Castilla · June, 2021

→ School failure in Spain: why does it affect boys and students of low socioeconomic status so much? · José Montalbán Castilla y Jenifer Ruiz-Valenzuela · September, 2022

→ Stress and depression during the pandemic: why gender inequalities, labor amrket conditions, and social protection matter · Dirk Foremny · December, 2020

Member of the advisory council of the Center for Economic Poliy - EsadeEcPol

View profile