The Gender Pay Gap in Spain: What Factors Contribute to Its Persistence?

Claudia Hupkau, Jimena Contreras

7 Mar, 2025

Spain has made significant progress in reducing the gender pay gap between 2010 and 2022, although substantial disparities remain. Our analysis of Spanish labor market data indicates a clear downward trend in the wage gap between men and women, alongside evidence that structural barriers continue to impede equality. The main findings are:

- Reduction of the wage gap: The unadjusted gender pay gap (difference in average income between men and women) has notably decreased. In 2010, women earned approximately 23% less than men annually; by 2022, this gap had narrowed to around 17%. In terms of hourly wages (accounting for part-time work), the gap decreased from 15% to 9% during the same period. This nearly halving of the wage gap represents substantial progress: 2022 was the first year Spain’s hourly wage gap reached single digits.

- Key factors behind progress: Improvements are largely due to increased labor market participation and advancement of women. Over the past decade, more women have transitioned to full-time employment and roles in higher-paying industries and occupations. These occupational and sectoral shifts explain much of the gap’s reduction (Martínez, 2024; Hupkau & Ruiz-Valenzuela, 2022).

- Persistent disparities: Despite this positive trend, a fundamental wage gap remains. The “unexplained” portion—differences persisting even after accounting for education, experience, working hours, occupation, and sector—

has barely changed over the past decade. Our analysis shows that even in 2022, when comparing men and women in similar jobs and with similar qualifications, women earn on average about 12-13% less per hour.

This suggests structural factors and subtle biases continue to disadvantage women. Specifically, as women increasingly enter higher-paying fields, wage inequalities within the same sector or role have become more apparent. In 2022, controlling for sector increased the calculated gap by approximately 4 percentage points, indicating that women are now well represented in high-paying industries but continue earning less than their male counterparts within these industries.

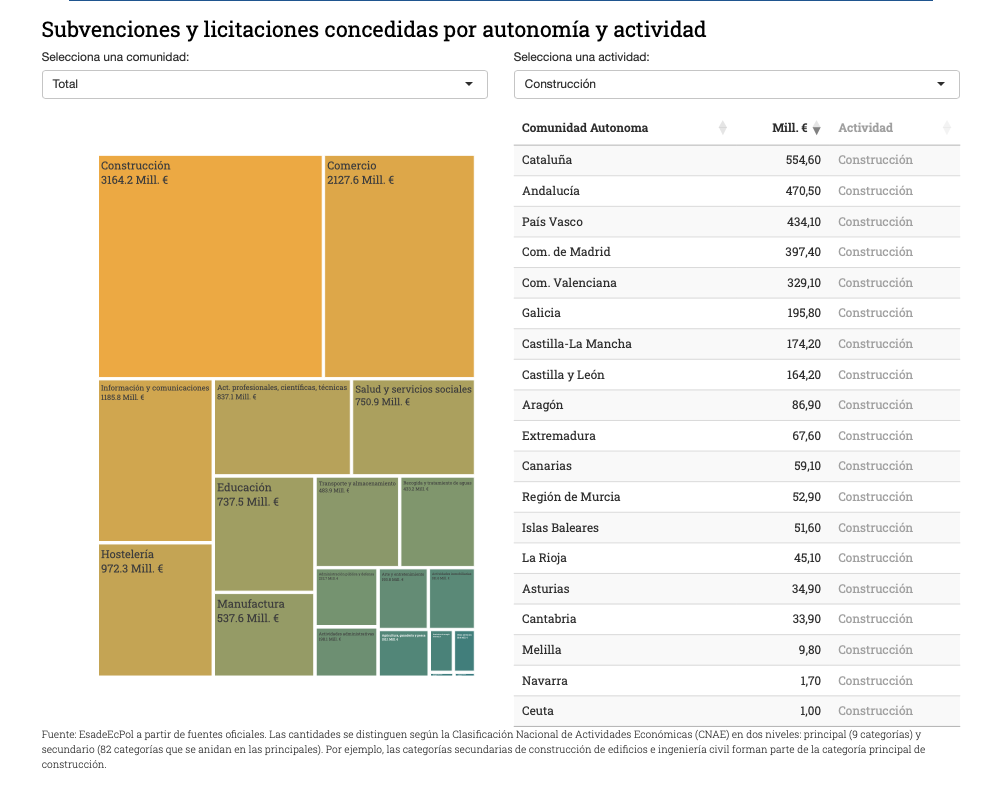

Wage gaps vary significantly across sectors: In transportation and storage, the gap favoring men is minimal (1%), whereas in health and social services, as well as professional and scientific activities—both strongly female-dominated sectors (56.2% and over 76% women, respectively)—the gap reaches 21%. Interestingly, in construction, where women represent less than 12% of the workforce, they earned, on average, 15% more than men in 2022.

However, sectors with minimal (or even inverse) raw wage gaps—such as transportation and construction—exhibit large adjusted gaps disadvantaging women, at 16% and 13.6%, respectively.

Our sectoral analysis highlights drivers behind these disparities:

- For instance, in health and social services, the significant raw gap (21.3%) shrinks when controlling for occupations, suggesting occupational segregation explains much of it. Yet, nearly half remains unexplained after considering company and individual characteristics. Similarly, in finance, around 42% of the gap arises from the concentration of women in lower-paid roles, with little additional explanation from corporate or personal characteristics.

- In other sectors, observable characteristics explain almost none of the differences. In public administration and defense, the raw wage gap is relatively small (6.3%), and controlling for occupations only slightly increases it (to 6.6%). Similarly, in hospitality, the gap shifts from 5.4% to 4.3% after adjustments. Such minimal variability suggests that sectoral wage disparities cannot be attributed to differences in working hours, occupations, or types of firms, but rather to deeper, often unmeasurable factors perpetuating gaps within these sectors.

- Conversely, in sectors such as construction, manufacturing, and energy (where women are a minority, typically holding senior positions), the wage gap widens when controlling for occupation, indicating a greater penalty within occupations.

One primary driver of this disparity is likely the “motherhood penalty,” referring to career and wage setbacks faced by women after having children. In Spain, mothers’ earnings decline sharply after childbirth (about 11% in the first year), with a long-term penalty of around 28% compared to fathers (de Quinto et al., 2020).

This lasting impact of caregiving responsibilities on women’s careers, along with glass ceiling effects in leadership roles, means equal pay for equal work is not yet a reality. In short, gender convergence has stalled at the final stage: after reducing the gap through improvements in education, experience, and access to better jobs, the remaining inequality is linked to more challenging issues like work-family trade-offs, implicit biases, and organizational culture.

Policy Recommendations: Specific policy actions are necessary to close the residual gap and maintain progress. We propose addressing both practical barriers faced by working women and underlying social norms:

- Support working parents: Expand access to affordable childcare and strengthen support for working mothers and fathers. Spain has already made a historic move by equalizing parental leave for men and women (Farré et al., 2024).

- Promote flexible and equitable working arrangements: Employers and governments should facilitate flexible work hours, remote working, and career re-entry programs without penalizing career advancement. Studies show that lack of flexibility disproportionately impacts women’s earnings, as shorter or discontinuous working hours often lead to significant wage penalties (Goldin, 2014).

- By restructuring workplace practices to accommodate various schedules (e.g., offering quality part-time positions or remote work), employers can retain talented women and reduce wage gaps. Importantly, these arrangements should be acceptable for all employees, not just women, to avoid stigmatizing mothers. Encouraging a culture where both men and women freely utilize flexible schedules or parental leave can help mitigate gendered biases (Hupkau & Ruiz-Valenzuela, 2021).

- Improve wage transparency and enforcement: Rigorous implementation of Spain’s recent salary equality legislation is essential. The 2020 Wage Equality Law (Royal Decree 902/2020) introduced wage transparency tools, requiring companies to maintain gender-disaggregated wage records, salary audits, and equality plans (Payanalytics, 2023). Data indicate these policies effectively reduce wage inequality (Blundell, 2021), especially relevant in sectors with low female representation and high unexplained gaps (e.g., construction, transportation, manufacturing, commerce).

- Address sectoral and occupational segregation and glass ceilings: Initiatives encouraging women in STEM careers and executive positions (both private and public sectors) can balance gender distribution across occupations. Mentorship, sponsorship programs, and bias training at workplaces are strategies to help eliminate glass ceiling barriers (Hupkau & Ruiz-Valenzuela, 2024).

Implementing these policies can help Spain build upon recent momentum and address the underlying causes of the persistent gender pay gap. Eliminating this gap would yield broad benefits—from increased household income security to a more productive and equitable economy—making it a priority aligned with social justice and economic efficiency.

Assistant professor at CUNEF & Associate in the Education and Skills Programme at the Centre for Economic Performance (LSE)

View profile

Economist focused on public policy, with a master’s degree from the Barcelona School of Economics and a bachelor’s degree in economics from Rafael Landívar University.

View profile